In his book, Korean Dream: A Vision for United Korea, Dr. Hyun Jin P. Moon observes that many of the early Korean independence leaders were motivated not merely by the prospects of self-governance, but by a deep calling rooted in the historic and cultural identity of the Korean people – to build a nation rooted upon the Hongik Ingan ideals and bring benefit the world.

In many ways, it was this high-minded vision that drove the optimism and passion of the Korean independence leaders. The fight for independence required the Korean people to undergo a process of transformation, forging a greater sense of identity and purpose in the founding principles of their people.

A picture from the 1920s of Ahn Chang-ho, also known as Dosan.

Ahn Chang-ho, one of the Korean founding fathers, expressed this very desire to a group of young independence activists. He said:

There will be the time when our Tae Geuk (Korean) flag will wave in cities across the globe. our flag will represent absolute trust and superb quality…but some day the word “Korean” will be synonymous with virtue, wisdom, and honor.”

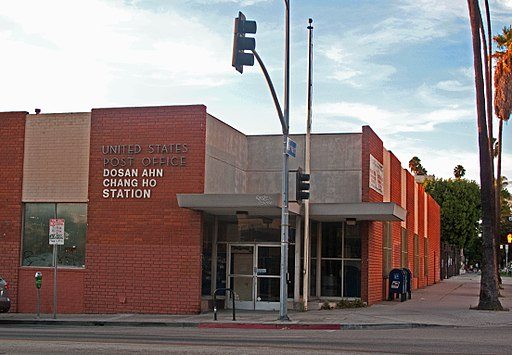

Today, Ahn Chang-ho, also known by his pen name Dosan, is recognized not only in Korea but also in his family’s adopted home just outside of Los Angeles in Riverside, California. There, his statue joins the statues of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi in front of the city hall. He also has a post office and freeway interchange named after him. He is honored as a global reformer and human rights fighter and founder of the Korean-American community.

From as early as 1897, Ahn Chang-ho would establish himself as a leader in the struggle for Korean self-sovereignty. In 1902, he would leave for the United States to further his education, but more than fulfill his educational goals, he became a galvanizing force in the Korean diaspora community before eventually returning to Korea to take up in earnest the fight for independence.

Ahn Chang-ho’s thought leadership lent much in the way of articulating the key elements necessary for such a successful transformation.

Of his many contributions, two key elements remain as essential lessons for us today as we continue to grapple with the ideal of one Korean nation.

Ahn’s Thought Leadership: Self-Mastery through Sincerity and Truth

First, was his emphasis on self-mastery through sincerity and truth. During Ahn’s time in San Francisco, he joined the Korean immigrant farming community, encouraging them to pour out their sincerity even in the smallest task. He was known to say, “Pick even one orange with sincerity in an American orchard will make a contribution to our country.” Later in Korea, he would instruct his pupils as follows, “Let all of us study sincerity. Let all of our people make a strenuous effort to become a sincere nation. This is the only means of saving our country.”

Wherever he went, Ahn established schools that sought to develop not just the skills of the youth, but their character. He believed that the youth of the nation were the most important national asset for a thriving nation that could benefit the world. He would ask his pupils at the Taesong School in Pyeongyang, “Do you love your country? Then you become a wholesome character first.” In his personal philosophy and leadership, he exemplified this creed, always sincerely seeking truth and moral development. He urged his students to first become “great men” who could then serve and lead their nation. He uncompromisingly criticized the shortcomings of his people, while highlighting the best qualities of the Korean people, gently chiding all the while encouraging, “Let us reform our lazy limbs and train them to become vibrant and diligent.”

Known internationally for his human rights work and dedication to the Korean-American community, Ahn Chang-ho even had a U.S. Post Office named after him.

Ahn’s Thought Leadership: Civic Engagement based on Responsibility and Common Vision

A second key element of Ahn’s thought leadership was civic engagement based on responsibility and a common vision. Ahn emphasized the need for a renewal of the Korean ethic in a way that would contribute to the entire global community. He challenged the Koreans around him to extend their inherent devotion to their family, clan and region, to encompass their greater community, society and nation.

The notion of a united Korean people has emerged at times of crisis in Korean history. The Tangun story of the founding of the Korean nation has been and should continue to be as a touchstone for the Korean people to awaken to their destiny as a people to create a model nation that would benefit the world. Yet, just as crisis has brought the Korean people together, divisions along regional and clan loyalties and social classes left Korea and Koreans bereft, unable to fulfill their noble calling. We might see the fight for Korean independence in the early 20th century as repeating this historical pattern, an opportunity for the Korean people to overcome these divisions and rally around the founding vision.

Ahn saw the necessary unifying force for independence as, simply, love. “Ideology does not hold a group together. Love does,” he wrote. A key concept that he introduced was “Chongui tonsu,” or cultivating a harmonious society based on love for one another. In action, this concept was essentially sustained civic and social engagement. In both Korea and in the United States, Ahn Chang-ho would establish societies that cultivated a sense of mutual responsibility and engagement that also served as fora where Koreans could explore Korean virtues and ethics as well as a unifying vision for independence.

In San Francisco, he and his wife personally visited the homes of immigrant Korean farmers to clean homes and teach families about hygiene and health. This grassroots outreach would create the foundation for the National Korean Association, which would help improve the living conditions of Korean famers and also improve relations among Korean and American communities. In Korea, he established the Shinminhoe, one of the most influential organizations for Korean independence.

More remarkable still was that he was able to extend his vision to include even though we might consider his foremost enemies, the Japanese people. He expressed his aspirations for friendly Japanese-Korean relations as an essential resource for the good of the entire East Asian region:

“I don’t want to see Japan perish. Rather I want to see Japan become a good nation. Infringing upon Korea, your neighbor will never prove profitable to you. Japan will profit by having 30 million Koreans as her friendly neighbors and not by annexing 30 million spiteful people into her nation. Therefore, to assert Korean independence is tantamount to desiring peace in East Asia and the well being of Japan.”

In this way, Ahn sought to create a united Korean identity through civic engagement by encouraging all Koreans to love one another. He saw that in learning to love and serve to one another, the people could develop the character, experience and education to then extend that same love to those around them and eventually, the entire world.

Today, as Koreans and the global community faces a critical juncture in history regarding human rights, nuclearization, development and more, we would do well to look back to those ‘giants’ who came before us. In coming to a better understanding of the Korean Dream, we can better formulate changes on the level of entire systems rather than band-aid type interventions and piecemeal solutions. We can pay tribute to Ahn Chang-ho and his work in service to Korea and humanity through our work towards the Korea of all our dreams.