Setting the stage for the March 1st Korean Declaration of Independence movement in 1919 was the brewing question over the issue of national self-determination in the post-WWI world.

In January 1918, the U.S. President, Woodrow Wilson, in his “Fourteen Points” indicated support for the principle of “self-determination” for colonized people. In it, he made pointed recommendations for an “independent Polish state” and the “absolutely unmolested opportunity of an autonomous development” for those currently under Turkish rule. In his closing, he spoke in unequivocal terms, declaring:

An evident principle runs through the whole program I have outlined. It is the principle of justice to all peoples and nationalities, and their right to live on equal terms of liberty and safety with one another, whether they be strong or weak. Unless this principle be made its foundation no part of the structure of international justice can stand.

And while he did not address Korea directly, his statements sparked hope and the beginnings of the civil-society-led movement for Korean self-determination.

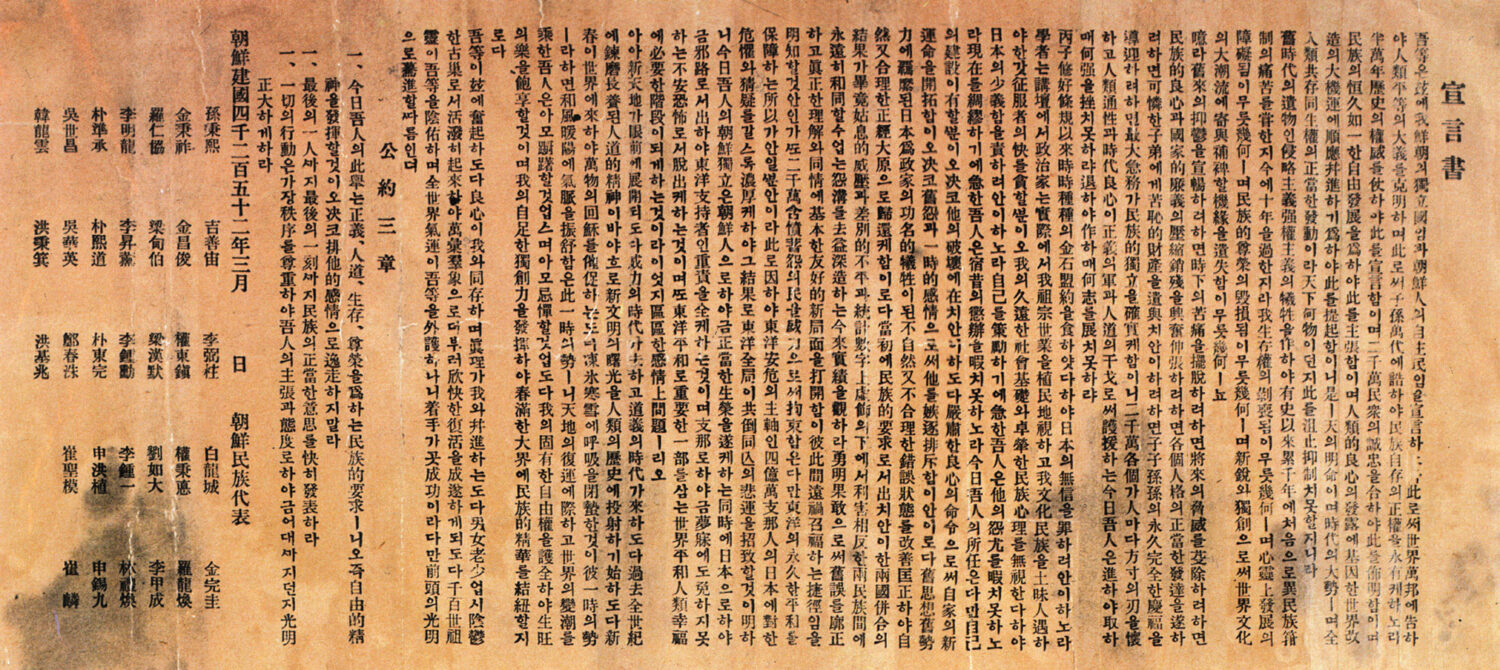

From among many similar efforts, one unifying statement that took hold in the hearts of the people was the pivotal March 1st Declaration of Independence. Even despite the many grievances of the people due to colonial rule, it was significant that this Declaration advocated an approach that does not “dwell on the sins of the past” but looked to empower the Korean people to build a model nation not only for their own sake but for the world. The following passage summarizes the essential spirit of the movement:

We claim independence in the interest of the eternal and free development of our people and in accordance with the great movement for world reform based upon the awakening conscience of mankind.

The March 1st Declaration of Independence stated that “righting the wrongs” of both the past and present was not only about the Korean people but about “Peace in the East.” Significantly, they foresaw how the end of a world of colonial rule and the “age of oppression by force” would bring forth an “era where principles reign.”

Preparations for the public reading of the historic statement had been ongoing long beforehand through networks of civil society groups throughout the country as well as abroad in the Korean diaspora communities in China, Japan and most significantly, the United States. On February 27, 1919, thousands of copies of the Declaration were distributed through schools and churches across the country. Following the first public reading of the Declaration on March 1st, the Korean people from all walks of life and backgrounds began to peacefully engage in an 8-month long movement across the entire Korean peninsula.

The 33 religious and spiritual leaders who signed the March 1st Declaration reflected the highest ideals of their respective spiritual traditions in seeking wholeness, unity, and self-transcendence. The movement that followed sought to uphold the peaceful ideals contained therein; the conclusion of the Declaration included, among three pledges, one that “all actions shall be respectful of order to demonstrate our honorable cause and rightful conduct.”

The 33 religious and spiritual leaders who signed the March 1st Declaration reflected the highest ideals of their respective spiritual traditions in seeking wholeness, unity, and self-transcendence. The movement that followed sought to uphold the peaceful ideals contained therein; the conclusion of the Declaration included, among three pledges, one that “all actions shall be respectful of order to demonstrate our honorable cause and rightful conduct.”

As we commemorate the efforts of the leaders in the Korean independence movement of 1919, we can also take care to learn the most important lessons of that time. In particular, we must not lose sight of the fact that the fight for independence was not just for Koreans alone.

Today, the spirit of the Korean Independence lives on in the Korean Dream movement as Koreans and their friends the world overcome together to build a free, independent, and united One Korea. In this, we further the effort not just to regain self-determination for all Korean people but help to realize the vision of the Korean nation cast at the time of its founding: to build a nation of high ideals that can bring benefit to all humanity.