While there are few direct links between the Korean Independence Movement and the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, the parallels between them are obvious. Both were movements in the struggle for freedom, responsibility, and self-determination. They worked in different contexts but significant figures in both movements ultimately advocated for the use of moral force and self-betterment as the necessary path for true liberty of the human spirit.

On the eve of the centennial of the Korean March 1st Independence Movement, we look to Thurman and some lessons that might be applied to Korean unification and reconciliation.

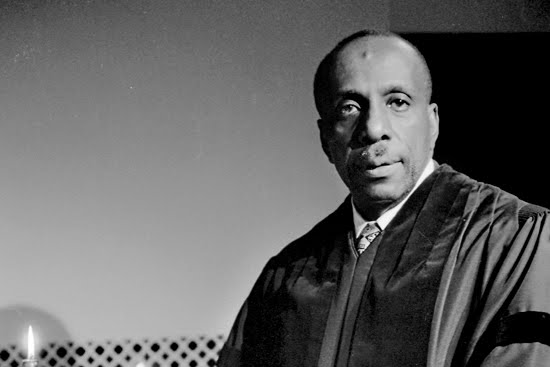

Howard Thurman: Theologian of the Civil Rights Movement

Howard Thurman was a famed civil rights activist, preacher, and professor at both Howard University and Boston University. He is perhaps best remembered as the theologian that helped Martin Luther King Jr. and other Civil Rights activists realize the importance and value of radical nonviolent resistance. King was reported to have carried Thurman’s book, “Jesus and the Disinherited,” which reportedly “became King’s civil rights bible, and he referred to it often for guidance.”

It was in Thurman’s notable book that we come across passages that touch on both the Korean thirst for independence and the American civil rights movement in the twentieth century. While he only makes a brief reference to the story that follows, the lessons in his book on the struggle for true and lasting freedom was relevant to the Koreans in their struggle for independence and perhaps even in the continuing saga of reunification and reconciliation.

Theology of the Disinherited

Thurman’s notable book, Jesus and the Disinherited

Thurman’s message was undoubtedly challenging to his audience, but individuals like Martin Luther King Jr. were able to take what was a paradoxical message–radical nonviolent resistance–and apply it to the issues of their day in demonstrably effective ways. In his book, he counsels to the “disinherited” that rather than becoming doubly enslaved with the anger, resentment, and hostility of being victimized, true freedom begins in the mind:

“To revile because one has been reviled—this is the real evil because it is the evil of the soul itself.” Jesus saw this with almighty clarity. Again and again, he came back to the inner life of the individual. With increasing insight and startling accuracy, he placed his finger on the “inward center” as the crucial arena where the issues would determine the destiny of his people.

And to explain this idea, he then recounts a story of when he was a young seminary student in the 1920s:

One afternoon some seven hundred of us had a special group meeting, at which a Korean girl was asked to talk to us about her impression of American education. It was an occasion to be remembered. The Korean student was very personable and somewhat diminutive. She came to the edge of the platform and, with what seemed to be an obvious emotional strain, she said, “You have asked me to talk with you about my impression of American education. But there is only one thing that a Korean has any right to talk about, and that is freedom from Japan.” For about twenty minutes she made an impassioned plea for the freedom of her people, ending her speech with this sentence: “If you see a little American boy and you ask him what he wants, he says, ‘I want a penny to put in my bank or to buy a whistle or a piece of candy.’ But if you see a little Korean boy and you ask him what he wants, he says, ‘I want freedom from Japan.’

Thurman understood this firsthand account of this young Korean woman to mirror the experience of the Jews at the hands of the Romans during the time of Jesus. While sympathetic to this experience as he had no doubt experienced this pain as his own, he took this opportunity to explore the true meaning and shape of freedom. Thurman elegantly weaves the words and experiences of Jesus at the time of colonial occupation with the experience of being black in America but concludes that freedom of the mind starts from understanding one’s identity and, as a result, the identity of even our enemies:

A man’s conviction that he is God’s child automatically tends to shift the basis of his relationship with all his fellows. […] One of the practical results following this new orientation Is the ability to make an objective, detached appraisal of other people, particularly one’s antagonists.

It is from this conviction, the idea that all humanity are the children of God, that enabled him to lay out a path to nonviolent resistance as the salvific force for all people–those that enslaved and were enslaved.

Lessons for Korea Today

AKU and entrepreneurship programs supporting North Korea women in their flower arrangement class

To refocus on the present day, we might say that, in some sense, Koreans in both the North and South are not free. Ironically, the captors in this scenario are not outside forces; the antagonists are within. North and South Koreans regard one another as both family and enemy and so we refer to the resolution of the division as both a process of reunification as well as reconciliation.

Having been separated for over 70 years, Koreans have, by and large, accepted the division of their homeland into two parts. Political, economic and social systems have been allowed to define a people once united by common language, culture, values, and stories, not to mention 5,000 years of shared history.

Today, we can see how the challenge for Korean reunification and reconciliation starts in the mind. It starts by asking the basic questions of Korean identity and destiny: Who are we? Where did we come from? Where do we want to go? It is from the answers to these simple, yet difficult questions that will light a way forward. This is the behind-the-scenes work that we must engage in order to realize the Korean Dream, articulated at the time of the founding of the Korean nation–to “bring benefit to all humankind”.

And this is true not only for the Korean people but perhaps for those people and nations who continue to grapple with difference–between race, religion, social class, ideology–as the basis for one’s own identity.

Will we take up the call of our time to become as One Family Under God? It is up to us to decide.

The One Korea Global Campaign is a grassroots-movement of over 1000 Korean civil society organizations working toward the peaceful reunification of the Korean peninsula. As the 100th anniversary of the March 1st Movement approaches, the campaign continues to draw support from Koreans in the North, South and diaspora for Korean reunification. Just as Korean-Americans played an important role in the Independence Movement, the campaign hopes to draw their support today to advance the Korean Dream, a vision for a free, unified nation that lives for the greater benefit of humanity.