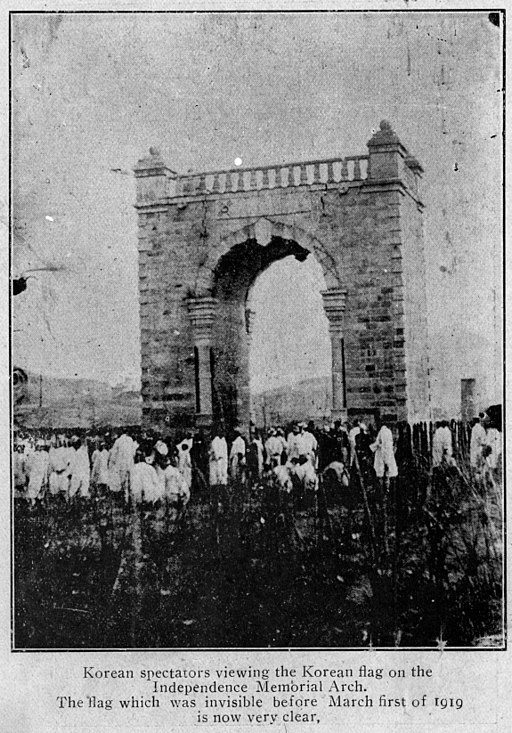

March 1 is a national Korean holiday established in 1949. It commemorates the events of March 1, 1919 when an estimated 2 million Koreans stood together to demand their independence and the dignity of self-rule.

Even while March 1st is the date that is commemorated, it was in fact a grassroots movement with a total of “1,542 demonstrations [held] across Korea over a three-month period. An estimated 2 million people, or about 10 percent of the entire population at the time, are said to have taken part.” Today, we can marvel at such a feat, which was accomplished under limited opportunities to organize or communicate to the masses and strict colonial policies regarding political activities.

Japanese historian, Masayuki Nishi, noted: “Back then, Koreans had no freedom of assembly or association. Nor were there media to convey the will of the people.” Yet under such circumstances, how was it possible to coordinate and conduct such a wide-scale movement? To answer this question, Nishi points to Shin Yong Ha, a distinguished professor at Ewha Womans University who explains, “religious organizations and schools took the lead because they were the only entities that were allowed to hold rallies without notifying the authorities in advance.”

Interreligious Unity in the Korean Independence Movement

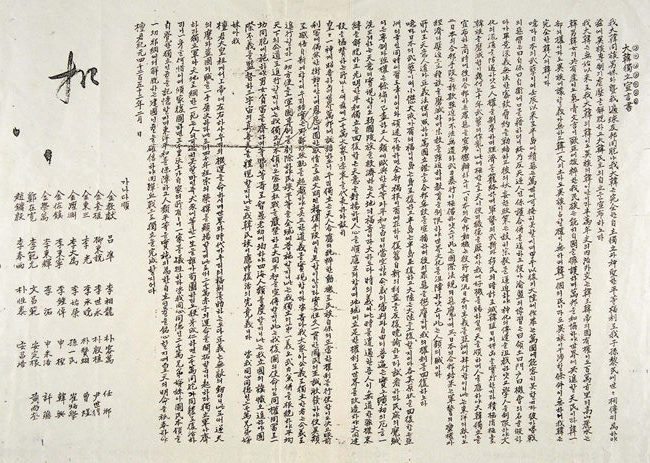

Interestingly enough, while much is made of the role of Christians in the Independence Movement, what emerges in the studies surrounding March 1 is that it was an inter-religious effort. All 33 signers of the Korean Declaration of Independence were religious leaders, representing an inter-religious alliance committed to Korean independence. The group was made up of Methodists, Presbyterians, Buddhists as well as the indigenous Korean religion, Chondogyo.

Korea’s spiritual landscape has always been considerably diverse and forming a consensus among these very different groups was made possible through dialogue and a commitment to a shared ideal. The spiritual leaders recognized the historic, global awakening of consciousness taking place after World War I that acknowledged certain universal principles concerning the value of individual rights and freedoms. The founding authors of the Korean Declaration of Independence were inspired by President Wilson’s 14 Point Declaration written at the close of World War I. They proclaimed the call for independence as the “solemn will of heaven,” and the religious leaders put aside their personal agendas, circumstances, and differences to stand with a higher vision and fulfill their duty to the Korean people.

A page from a Red Cross pamphlet on the March 1st Movement

What is not often written about is that the process of writing the Declaration took years of dialogue and deliberation amongst leaders of the different faiths. Initial efforts were stifled by disagreements between Christians and those of Chondogyo. Yet, while there continued to be differences of opinion, religious leaders recognized that without a unified effort for independence, the movement could not succeed.

They met to identify common issues and shared values upon which they could create a plan together for the March 1 movement. From their shared commitment emerged a concerted, grassroots effort driven by the various religious communities that put in the time, resources and manpower to support the independence movement. Rev. Soon Hyun, one of the original representatives of thirty-three Korean leaders who signed the Declaration of Independence writes, “March 1 showed the outcome of several decades of schooling and civic discourse concerning enlightenment and social reform, which heightened the sense of national unity as well as the thirst for independence.”

Much of the education took place within the religious communities who trained their leaders to become teachers who developed “a strong collective consciousness and will” in the Korean people. The religious communities became a natural place to educate and mobilize people. Chondogyo reports years of planning and training that took place in their monastery and religious communities leading up to the March 1 demonstrations. The connections within the communities were also used to raise resources to fund independence efforts.

Seoul, Korea’s Pagoda Park in the 1930’s

Faith leaders and the commitment to non-violence

It is also important to recognize that the faith leaders played an important role in ensuring the non-violent nature of the March 1 demonstrations.

The significance of this commitment to peaceful demonstrations can be understood when we look to a pre-cursor of the March 1 declaration made on February 8, 1919 in Tokyo, Japan. A considerably younger group of Korean students studying in Japan wrote out a declaration that concluded, “If our demands are turned down, we will fight an endless bloody war.” While we can debate the reasons why this declaration failed to gain traction, it may be in that the vengeful tone did not resonate with the spirit of the Korean people and lacked the moral authority of the religious leaders.

Instead, even despite the grievances imposed on the Korean people, the March 1 declaration advocates an approach that does not “dwell on the sins of the past” but looked to empower the Korean people to build a model nation for the world. Ultimately, we might surmise that the moral authority of the religious leaders and their peaceful aspirations for their nation ensured that the demonstrations were dignified and motivated by a higher purpose.

Lessons for Reunification

Although the dream of independence was never fully realized at that time, the Korean Independence Movement offers insights that could become a touchstone for our efforts for Korean reunification today.

We must reflect and ask difficult questions including:

- What hampered the Korean Independence Movement of the past?

- What can we learn from those efforts?

- How can we define common agreements that cut across lines of identity?

- What is it that we ultimately want to build together?

- What are the ideals that can bind us together?

- What is the Korean Dream?

In this historic time, will spiritual leaders and faith communities once again come together to play a critical role in advancing reunification and realizing the Korean Dream?

Revised on March 12, 2018.